Among the many things I do for a living, I write. I’ve been writing professionally for over five years now, and my writings – like this text – have always been in English.

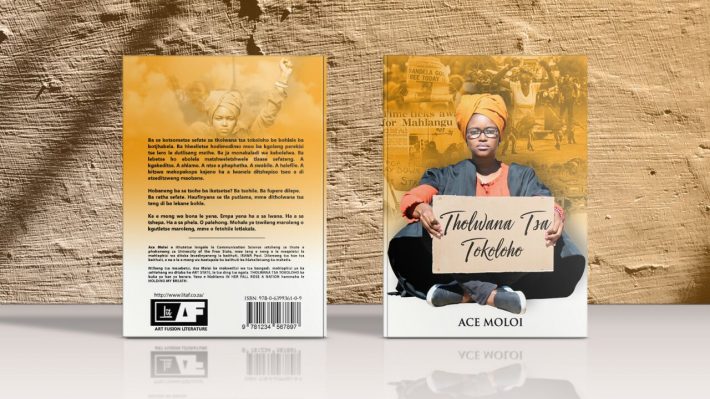

But this year I find myself holding my breath for my third book, which is a variation from the norm: it is a Sesotho book called Tholwana Tsa Tokoloho. It is an anthology of short stories, which I would like to think carries humour, education, political consciousness and love.

I have recently unveiled the cover of the book, which is brightened beautifully by an up and coming model and radio presenter , Portia Sebothelo. As displayed on the cover, this is a book that interrogates the whereabouts of the fruits of our freedom, from different angles.

But this is not the cornerstone of my note to you today.

The thinking behind this text is correctly explained by my reasoning when people ask, “ Why a Sesotho book, and how has the transitioning been?”

I would like to believe that I haven’t transitioned. If there ever was a crossing of floors, then it must have been from Sesotho to English, mainly and plainly because I have always expressed myself in Sesotho first, before English.

Not long ago, the world celebrated the importance of the mother tongue, and I too found myself pondering the meaning of Sesotho to me as an intellectual, writer, artist and commentator.

At Lesotho’s Ba Re E Ne E Re Literature Festival, the organisers boldly decided to host one of the sessions strictly in Sesotho as a step towards the revolutionary dream of decolonising the space. There, I realised that it’s actually very necessary for us as Africans to narrate deep philosophical and political speech in our own languages.

Before then it had never really occurred to me that we can facilitate a conversation about phenomena such as decolonisation in an African language and actually make sense.

Although my new Sesotho book was not birthed by the spirit of the literature festival, the festival nevertheless inspired a sense of urgency to sit down and work.

But I was cautious not to turn my book into any other ordinary Sesotho project. My grievances about Sesotho literature, which I shared in Lesotho and later at the Free State Literature Festival and other platforms, were that we need to sync Sesotho writings with current times.

We cannot go on behaving as though Basotho can only write about traditional affairs. We are complex human beings who don’t only exist to reject modernity. We can write a sex scene in Sesotho. We can go on a politicking tangent in Sesotho.

This of course requires of us to invent new words so that we keep up with the changing times.

It further challenges us to make reading and writing in our own language not just a cool trend for Twitter, but a lived principle for the advancement of our nation.

Necessarily, we have to plant the seed at lower grades the same way my mother passed every Sesotho book to me when I was a kid.

With this note, and the publication of Tholwana Tsa Tokoloho, I don’t by any means seek to portray myself as a righteous mouthpiece for Sesotho-speaking people (the fact that I’m writing this in English says a lot about my sinful nature). If anything, I hope my humble contribution to the new age will make just one Mosotho fall back in love with our literature again.

It is with the privilege of tholwana tsa tokoloho that I hereby present to you another edition of ART STATE.

Freely,

Ace Moloi.