Mabaphile: Thapelo ya Dikgwahlapa

Mandisi Dyantyis’ performance of his hit hymn Mabaphile at The Soulful Soirée took ART STATE publisher Mpho Matsitle all the way back to church. He shares his revelations.

No matter the occasion, no matter who is on the pulpit, it could be the Son of Man himself delivering a sermon, it wouldn’t matter. When the clock strikes midday, sethoboloko, on any given Sunday, the bells of the St John’s Apostolic Faith Mission will toll. Moments before the hour, Thapelo, who has his throne by the door as Khosa ya Monyako, would surreptitiously exit the chapel towards the belltower.

Thapelo is a character in my work-in-progress novel/la with the working title Bana Ba Metsi. He is one of those characters that was supposed to add colour to the story, then disappear. A throwaway character, who wasn’t in any of the notes made when mapping out the contours of the story, yet refuses to be so reduced. He will be heard. (To garner the sympathies of the reader, I hasten to add here that Thapelo has complicated the planned story so much that the novel/la has grinded to a halt.)

Thapelo is not alone as such a character, there are many who society wishes to chuck by the wayside. Who once a while make the headlines to colour our otherwise stale lives, provide content for discourse, and offer us an opportunity to put on display our generosity. But who otherwise matter very little to us, and who we’d rather forget about sooner than later. Think Life Esidimeni, think Marikana, think 80 Albert Street. These are what my Marxist-Lenist-Fanonian friends would call the lumpenproletariat or the wretched of the earth. “Abahluphekayo,” Mandisi Dyantyis calls them, “abangenathemba.” In the parlance of St John’s; dikgwahlapa.

Thapelo, as he is revealed to me, is one such damned soul. He comes to the church in chains, having been rescued from sure death at a mental institution. Barely a teenager, he is recently orphaned, homeless, drug addled, and suffers from violent schizophrenia – which one of the prophets in the church ascribes to him having swallowed his twin in their mother’s womb. Through the patience of the prophets, basebeletsi and batlhatlhobi who never tire of singing him Mabaphile, hard labour, and religious routine, Thapelo is healed and earns the important role of doorkeeper and bellringer.

Thapelo clasps the chain lever tightly in his right hand and looks up at the sky. He clears his entire being off all impurities, ditomoso, as he focuses solely on the task at hand. His watch beeps, and he yanks on the chain to ring the bell. Tshebeletso ya Moya is such that people often lose track of time. But such tardiness is the province of mortals, Angels are always on time. And at midday everyday they descend to the world of the living to collect prayers. So when the 12 o’clock bell rings during the Sunday service – mid-song, mid-sermon, mid-ritual – bana ba metsi drop everything, and fall to their knees in fervent prayer. When everyone is done with their individual supplications, the priest will lead Thapelo ya Dikgwahlapa, a prayer for the wretched, enjoining the faithful to send prayers with the Angels to heaven for those that cannot pray for themselves, so that nabo mabaphile.

A re rapelleng ba ntlong a lefitshwana

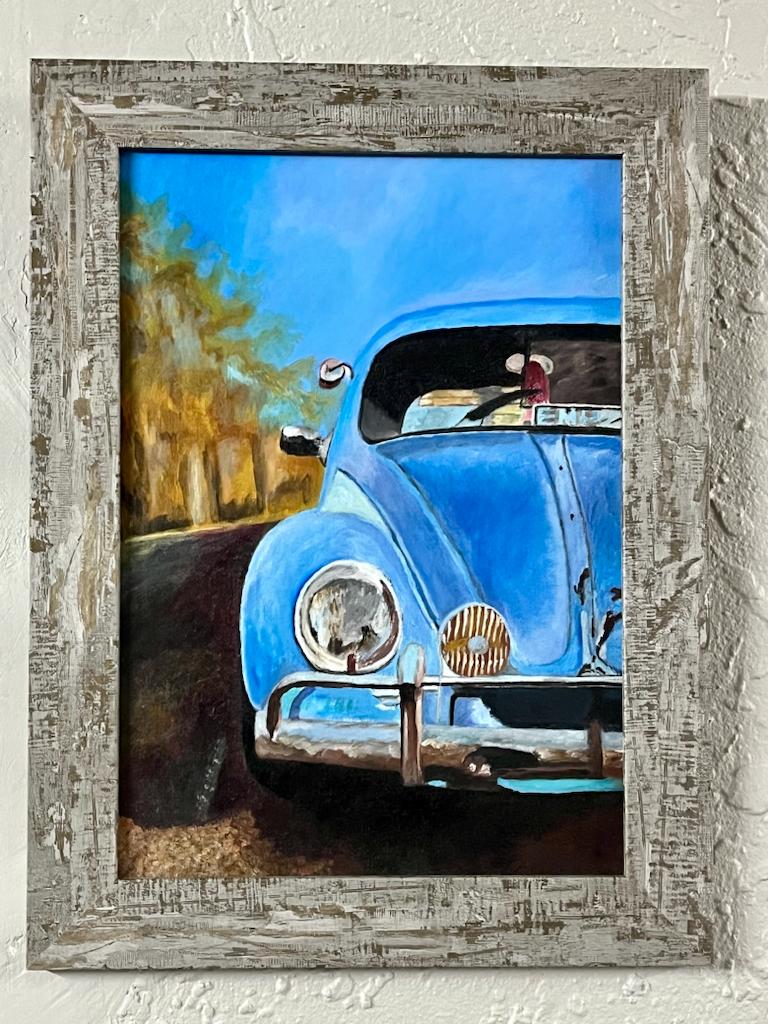

I recently bought artwork from the William Humphreys Art Gallery. The painting is by an inmate at the Kimberley Women’s Prison, from a project run by the Gallery in collaboration with the Department of Correctional Services. It is a beautiful work of a blue VW Beetle on the road. The acrylic on board painting is vibrant with character, the car seemingly belongs to a tlhakodimaje – a wanderer – like me, the colours are a calm melancholy, betraying a deep yearning for freedom. It is Chapman’s Fast Car, a ticket out of here. I bought the painting because it spoke to my soul, because it was to my taste, and because it was ridiculously affordable. That my purchase was contributing to the rehabilitation efforts for offenders, that my purchase also moonlighted as a prayer that those in the dark house, abangenthemba, mabaphile – none of that offended any of my sensibilities.

But, I soon found out, we are not all children of the same mother. One of the attendants tells me that a patron who wanted to buy the same piece pulled back upon discovering that the work was painted by an inmate. Apparently the said patron had some choice words about these lumpenproletariat, and none of them was anything close to mabaphile.

No matter what a bad day it might have been at the office, I cannot imagine a situation where a priest would forget the prisoners during Thapelo ya Dikgwahlapa. Them, the widows and the orphans, would always get a mention. With the prisoners, emphasis is always made to pray for the innocent and the guilty. The former, so that their innocence might be proven. The latter, for rehabilitation. But to all, in equal measure:

Sithi Mabaphile!

Mabaphile!

Mabaphile!

Mabaphile!

Sithi Mabaphile!

Sithi Mabaphile!

Sithi Mabaphile!

The High Priest of Jazz

Singer-songwriter, composer, and trumpeter Mandisi Dyantyis has built himself a cult following, informally called amaDyan. I am not ashamed to count myself among these followers. However I was not, I am ashamed to admit, an early adopter. Although he came out of “nowhere” – in the sense that he hadn’t featured as a session player to any of the big name artists as is often the case in the jazz tradition – his mark on the landscape was immediately noticeable.

His debut album, Somandla, did not escape me. It was all the rave on my WhatsApp statuses feed. And from contacts whose taste in music I share. However I struggled to listen to the album. Or rather, to hear it. That was until one day I came across a video of Mandisi conducting a church choir. His passion there inspired the character Sizwe in the novel/la, also a choir conductor. But most importantly, seeing Mandisi deep in the spirit, opened a new channel through which I could commune with him. I went back to Somandla, and as the priests always advise before the reading of scriptures, I listened ka ditsebe tsa moya. And just like that, I was initiated into the cult.

If splitting hairs is an exercise one is wont to, Mandisi’s lyrics can be broadly divided in two: the personal and the political.

Somandla, in contrast to the sophomore Cwaka, balances the two and is less lyrical. The title track beseeches the Almighty to intervene in ills noted in Kuse Kude and on my favourite track Esazalwa Sinje, which for me captures the Fees Must Fall moment aptly. On Cwaka these political songs only find lekaelagongwe in the toyi-toyi song Ziyafana.

The personal lyrics can be further divided in two; love songs and those that minister to the soul. On the former, Cwaka offers Ndixolele and Isithandwa Sam as the sad spinster bridesmaids to the belles of the ball Molo Sisi and Ndimthanda, which have already reached classic status.

The majority of the songs are Mandisi at the pulpit, ministering to broken souls. His own, in dealing with grief for his mother in Ingoma Yenkedama (Somandla) and NguMama and Isigidimi (Cwaka) and for his friend in Zamile (Cwaka). Iinzingo, which opens this oeuvre in Somandla, sees him echo Louis Armstrong’s Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen, whereas Kode Kube Nini, like Impumelo in Cwaka, decries the delay in the answering of prayers, echoing #361Sioneng:

Ha o hauhela batho,

Nkhauhele le nna.

Jesu, Jesu, kea ho rapela,

Ha o ntse o sitsa ba bang,

Se mphete le nna.

Cwaka is a treasure trove of this ministry. The title track borrows from Exodus 14:14: “uYehova uya kunilwela, ke nina niya kuthi cwaka.” Ndiyakholwa and Ungancami implore one, no matter the circumstances, as Rudyard Kipling advised, to

“force your heart and nerve and sinew

To serve your turn long after they are gone,

And so hold on when there is nothing in you

Except the Will which says to them: ‘Hold on!’”

This ministry to the soul can be summed up in one word, in one refrain: Mabaphile. All these songs are an elaboration of those “abasindwayo”, “abanemithwalo”, “abengenathemba” and “abehluphekayo”. It is to them that Mandisi ministers to. Those weighed down by burdens, those who are hopeless, those who are suffering. In short; dikgwahlapa.

Much like the priests who lead Thapelo ya Dikgwahlapa, Mandisi knows very well that it is only communal prayer that can deliver this healing. Hence the “we” in the song is not a royal we but an invitation – demand even – that we all join in the prayer. This prayer though, is not a supplication. The wording at the very least betrays that it is a commandment. To water it down in translation: “We say let them live/heal!” In today’s pop spiritual parlance, he is manifesting healing. This prayer, this manifestation, this demand to be heard and to heal/live, is our version of Jacob wrestling with God and not letting go until being blessed.

umGowo: The Pandemic

On the stage recently at The Soulful Soirée hosted at the Oliewenhuis Art Museum in Bloemfontein, Mandisi expanded the definition of dikgwahlapa deserving of this benediction beyond those already mentioned in the albums. In a performance that triggered the memory of Thapelo ya Dikgwahlapa, standing at the edge of the stage in the unsurprisingly chilly September evening, he raised his hand as would the pope from his window blessing the pilgrims, and called out, one by one, the troubles that plague/d many of us in the audience:

Those who are financially distressed (interest rates much): Mabaphile!

Those who are gowishing because of mjolo: Mabaphile!

Those who are unwitting side dishes: Mabaphile!

Those who do us dirty: Mabaphile!

In as much as laughter preceded our chanting of “mabaphile“ in response to all these pandemics Mandisi manifested healing for, none of us would think these are laughing matters. Afterall, losologolo ditshego. A quick scroll on X, née Twitter, would show what ugly beings we have become, and the hurt we cause each other, all because we haven’t healed from our real and imaginary traumas.

Mabaphile bonke abantu

Indeed, grace extends to those who wrong us as well. It wouldn’t be stretching Mandisi’s prayer that “mabaphile bonke abantu” to include incarcerated offenders. I take from the insistence of the St John’s liturgy to distinguish between the innocent and guilty proof that there is no attempt to sanitise nor even excuse the crimes of those justifiably imprisoned. Neither is the William Humphreys Art Gallery nor the Department of Correctional Services “supporting criminals”, as the offended patron charged. It is a recognition of their humanity above anything else. As John Oliver insisted in an episode on healthcare for offenders; “the fact remains, prisoners are people. A hundred percent of them are, in fact.”

In Mabaphile, Mandisi Dyantyis implores us all to be Sankarian and wish only life to those who wish us death, to remember that those who wrong us may not even be aware that they need healing from amanxeba inflicted by countless others over long periods. I hope the gallery visitor who refused to buy the artwork due to their inability extend grace beyond the limits of their comfort soon learns this lesson. And to them I also say mabaphile. But – lying has never been my vocation – their loss has been my gain, I am a proud owner of the beautiful artwork they rejected, and for that I am glad.

FEATURED IMAGE: Mandisi captured capturing his captured self. Credit: Mandisi Dyantyis Facebook page.