Editor’s Note: The Stage’s a Pedestal

Ace Moloi writes about mental health in the creative space

Abstract

Tuesday, 10 October 2017, was World Mental Health Day, with particular focus on mental health in the workplace. In observance of this day, much has been said and written to correctly encourage managers to prioritise the wellbeing of employees.

With depression and anxiety ranking high in the corporate environment, huge amounts of money are estimated to be lost annually to slow productivity, presenteeism, absenteeism and other depression-inflicted wounds.

As I was listening to Martin van der Merwe’s The Big Breakfast Show on OFM, specifically his interview with Dr Ian Westmore, I couldn’t help but wonder what percentage of the mentally unhealthy employees is taken up by artists who need the salary, yet despise the office days of their lives.

How many of them do the work for a living, but aren’t living for it?

Essentially, is anybody interested in tackling mental illness in the creative community where depression and anxiety are so rampant?

My truth

“I’m retiring from book festivals,” I said to my landlord with a tone rich in hopelessness. It was a day after the 2017 Free State Literature Festival, in which I was invited as the youngest author on the line-up.

It was not the first time I commit to quitting the literary space. In December, 2016, I returned from Lesotho’s Ba Re E Ne E Re Literature Festival with this resolution, as the void was becoming increasingly impossible to bear. Actually, Lesotho itself was a follow-up on an increasing sense of emptiness that I suspect first announced itself at the 2016 Open Book Festival, held in Cape Town.

I don’t think this feeling was present in the aftermath of the Rosebank-based Kingsmead Book Fair, or the locally organised Matjhabeng Book Fair. I was not yet psychologically woke.

So I understood where my landlord was coming from when she asked for a specific incident that could have sealed my decision to withdraw from literature gatherings.

“It’s just that when the day ends and everybody goes home, the loneliness becomes too unbearable,” I tried to explain myself to her. “I always perform at my best in book discussions, but the applause I get doesn’t match my material reality.”

“It’s a performance. I perform depth for the audience. I retell my pain. They clap hands and go back home to live their lives. They don’t care about me,” I remember myself saying.

“But don’t you need book festivals to market your book?” she went for the undeniable.

Thing is, with other literature events I used to just hint at post-event hollowness without the courage to state my heart. Or, perhaps, I never understood my own feelings. Although I knew something was wrong, I never knew what was wrong.

So, on this day, I decided to tell the truth; the whole truth and nothing but my truth.

The stage is a pedestal

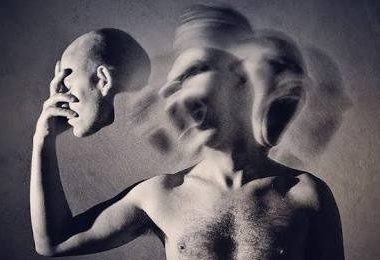

Every performance is followed by an existential crisis of its own match. The stage momentarily puts artists on a pedestal of significance.

For the duration of a club DJ’s set, everybody dances to their tune. When you look at them on the decks, you see joy, contentment, pride and a sense of purpose. On the rare occasions that I’m in the club scene, I always marvel at the deejays. But, as if to burst my own bubble, inevitably wound up praying for them to be strong after the event, in the solitude of themselves, in the innermost rooms of their souls.

I think my own post-event depression has sensitised me to the unspoken sufferings of other artists.

If the stage is a pedestal, I think to myself, who will catch this radio presenter when the show ends?

Value for virtue

For artists to impart value, virtue must depart. When an artist performs, the performance goes beyond physical exercises. There is something intangible, something incalculable, which departs from them so that whoever is watching can be entertained, healed, fulfilled. An outpouring of sorts.

When a poet contemplates a poem, they dig deep into the dark parts of their souls to find a revelation. At times, perhaps more often than not, what we appreciate as profound poetry is in fact a cry for help: a call sounded in loneliness, a suicide note, a relived trauma.

As an artist, your art is your soul. You pour yourself into it wholly, so that whoever encounters it feels personally targeted. You cannot impact anybody’s life with your art if its artistry lacks emotion. Emotion amplifies the sound of your work. Yet, unfortunately, emotion is costly. For your work to be emotive, you must perfume it with yourself: your story, your pain, your fears, your scandals.

Remembering my mother

In the process of writing my book (Holding My Breath) I revisited painful moments in my past which I had never thought about in ages. The book, as you may know by now, is a conversation with my mother, who migrated from this earth in 2005.

The circumstances in which we lived, before and after her passing, left no room for me to mourn her. From the actuality of her death until at least 10 years later, I pushed her far from recollection. As far as I was concerned, I didn’t know her: she never existed.

Of course such is the existential conundrum of blackness—our material conditions do not allow us to wallow in self-pity and trauma. There’s bread to fight for. There’s poverty to escape.

In my book I have outlined my relationship with my mother in the most accurate of details. But in summary, we were best friends, and fashioned ourselves as if I were her daughter. As a mother to two boys, in the absence of the father, she had to convert one of us into a girl in order to ease the burden of womanhood on her shoulders. As a result, I became the domesticated personality.

As is a relationship between a mother and a daughter, we too shared intimacy, secrecy and love. Losing her, thus, posed two diverging paths to me: (1) forget about her and keep fighting or (2) stay attached to her and remain in grief. My resolution favoured erasure over memory. I denied my mother.

In his novel, DANGEROUS LOVE, award-winning author Ben Okri attempts to depict the despair of loss through his artist protagonist who, many years after his mother died, still contends with her memories.

Of this remembrance, Okri ponders:

How does one remember a mother who has died? By her face? Her eyes? As a half-forgotten selective series of acts? Her voice? Or a spirit, a mood that never leaves?

The exploration of my mother’s legacy was as liberating (from disguised denial) as it was emotionally dangerous. Writing about my mother, her days of near-death, her burial and legacy shook the pillars of my sanity with a Samsonite intensity.

To date I still admire my book and ask myself, “Ace Moloi, where did you get the strength to do this?”

To self-fill is to mis-fill—seek help

Strength is of, and from, God. Artists are vessels of God. They are messengers. I follow almost every pastor you can think of, especially those who lead major churches. The other day I was watching a sermon by T.D Jakes and he was preaching on the same subject of value for virtue, saying that when he finishes ministering to his congregation, he feels emotionally and spiritually drained. He is empty, and needs a refill.

This I know to be the experience of many a preacher.

Artists are preachers. Art is fundamentally spiritual. Those who practice it cannot avoid spiritual warfare. It is therefore of great importance for each artist to have a relationship with God. It is not by an orgy of promiscuity that you will redeem your happiness. The thirst that frogmarches you to a drinking hole is actually a hole in your spirit: a thirst for God.

As a vessel in the hands of God, you can’t refill yourself. No vessel ever can. To self-fill is to mis-fill: it is to extinguish fire with petrol. In God, in Christ, you will find peace which transcends human understanding (Phil 4:7; Psalm 29:11; Col 3:15) and contentment with godliness (Phil 4:11 – 13; 1 Tim 6:6 – 12; Proverbs 19:23).

Work your health up

As a Christian who functions in the arts, I know better that faith doesn’t grant anyone immunity from hauntedness. Faith itself is validated by works.

Therefore, believing or not, we all need professional help. The first person on the queue when a psychologist opens their practice has to be an artist. Nobody needs mental health attention as aggressively as we – artists – do. Artists are the tormented of the earth.

Beyond counselling and a vibrant prayer life, we need to take care of ourselves as artists. Let’s do our best to stay healthy through exercise, meditation, conversation and peer-to-peer affirmations.

Macufe and the crisis of being

This entire edition of ART STATE, which I’m honoured to preface, is dedicated to the recently held Mangaung Cultural Festival (Macufe). Inside this special compilation you, our faithful reader, will find reports about various shows held under the banner of Macufe the 20th: Macufe Jazz, Macufe Comedy, Macufe Crafts Market and more.

Among its many capabilities – heightened excitement, flamboyant expenditure, wild behaviour and a generally good vibe – Macufe tends to also engulf local artists in a cloud of anguish. It is often a period for self-contemplation, which sometimes results in negativity, self-pity, bitterness over “missed opportunities” and the deadly peril of comparison—the shattering realisation that they have been exploited in relation to their handsomely rewarded Gauteng counterparts.

Now that the business of busyness has died down, it’s time for feelings of existential interrogation. Everything looks like it’s falling apart.

The city is corpsy, the bills are noisy, the neighbours are nosy, the temporarily AWOL girlfriend now wants to be cosy, and the official responsible for processing the invoice is lousy.

Was it worth it? Art: is it worth it? My life: who cares?

The South African Depression and Anxiety Group (SADAG) is Africa’s largest mental health support and advocacy group. Contact their 24hr helpline on 0800 12 13 14 and their emergency suicide line on 0800 567 567. Alternatively, you may SMS them on 31393 (and they’ll call you back), or tweet @TheSADAG.

Ace Moloi is the Editor of ART STATE. Keep in touch with him on Twitter: @Ace_Moloi